In this episode of Discern Earth, I speak with my good friend and forest carbon scientist, Elias Ayrey, about how scientific values shape his ethics, his fascination with paleobotany, how examining forests using remote sensing colors his view of the natural world, why carbon markets suck, whether voluntary action can tangibly mitigate climate change, and how he ended up starting his YouTube channel.

Transcript

David Valerio: Howdy, my name is David Valerio and this is Discern Earth, the podcast where I ask people who work in nature and climate about why they do what they do. Today I have on my good friend, Elias Ayrey. Elias is a forest carbon scientist with deep expertise in voluntary carbon markets. He's currently the Chief Science Officer at Renoster, which is the company that I work at. Elias, if you'd like you can give a more in-depth intro, otherwise we can get into it. Either way.

Elias Ayrey: Yeah, thanks so much for having me. My name's Elias. I'm a forest scientist by training, I have a PhD in forest science, but it's mostly focused on remote sensing. That is, basically evaluating forests using satellite imagery and whatnot. I am Chief Science Officer at Renoster, which is a carbon diligence firm. We evaluate whether or not carbon credit claims are genuine. I'm also a co-founder, and I've been in the carbon markets for about five years now.

David Valerio: Awesome. Well, now I'm going to open up with a really deep question. Are you religious or spiritual at all? And if so, how would you describe your relationship to the divine and how that influences your work on nature?

Elias Ayrey: I'm sorry to say that I'm not. Actually, I come from a pretty long background of atheists. I only have one grandparent who actually is religious. So I grew up not religious, and I stay that way today.

David Valerio: Wow, that's remarkable that your family has had that long a history of atheism. What's your family background? Where are they from?

Elias Ayrey: Well, I guess on my mother's side, they were physicists. My grandparents were. My great-grandparents were Jewish. But, you know, physicists are often not very religious themselves. And then my father's parents were religious, but he's not and of course neither is my mother having been raised in an atheist household.

David Valerio: Interesting. Well, it's a good thing I have an alternate question related to this. Given no religion, you know, does political ideology or political philosophy… Like what sort of what grounds you in what you care about and your values beyond religion?

Elias Ayrey: I mean I'm pretty left-wing and I've like done some like minor volunteer work for Democrats in the United States. I wouldn't say that that motivates me. I don't think that I need a religion or a political ideology to motivate me to do something about climate change. I think that that is something that we are all facing as a society. And being one of the biggest challenges of our generation, I think that that itself is enough of a motivation.

David Valerio: Yeah. So like maybe climate change is such a big problem instrumentally to humanity, regardless of what your grounding metaphysics is, that it's something that you would work on absent that sort of grounding. Does that make sense?

Elias Ayrey: That's what I would argue. I think of myself as a scientist first. I don't really think of myself as having much more of an ideology beyond just being very enthusiastic about science.

David Valerio: Well, that's a good thing because I wanted to sort of dig into that. How you fell in love with nature, how you got into forest science, how you got into science to begin with. Would love to learn more about your personal history there.

Elias Ayrey: That's an interesting question because I think there's probably a couple answers. I think first of all, most forest scientists you'll meet are pretty introverted people and I think that a lot of introverts like myself kind of find solace in the forest. You know, going on long walks by ourselves and communing with nature and learning about it. At a more personal level, my mother was a science teacher, a biology teacher, when I was growing up. So I think that that was a big motivator for me. She always used to run the experiments that she was running with her students on us first, on her kids first, to kind of see like if these were good lesson plans and stuff. So I think that's where I got my enthusiasm for both nature and science.

You asked why forests in particular? Apart from just really enjoying spending time in forests and feeling very at home, I think as an undergrad I really wasn't fixed to any one discipline of ecology. I was just generally interested in ecology. I settled on forests, but after like sampling a couple of other options. As an undergrad, I was an intern for the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration for marine biology and I spent a summer on a boat off the coast of Long Island. It was a very small boat, maybe a 30-foot boat, going up and down on 15-foot waves. I spent most of that summer completely nauseous and surrounded by smells like ether and dead fish, and I decided that forest ecology was much more interesting than marine biology.

David Valerio: Amazing. Yeah, I sympathize with that general interest in science and not necessarily being tied to any given one. Growing up, I was always a lover of nature. I grew up in Houston, as I think you know. It's a concrete jungle. But there's a lot of good nature around here. You know, I loved it in that capacity, but then going into undergrad, it's just like, I'm interested by so many things in the world that it was hard for me to pick one. But somehow I got into geology, partially because I'm a big fan of human history. And then geology, of course, is the history of the world on the longest timescales. And that's how I got into it. I like to think about, you know, what if my mom was a biologist? Would I have been gone down the biology track or what other avenues of natural science would I have gone down? Could I have not even gone down the natural science path? I don't know.

Elias Ayrey: Yeah, I think I probably also in some sense grew up in a concrete jungle, because I grew up in New Jersey. And when I got to college, I really found more of a love for nature than I had ever had before because I was at a college that was surrounded by beautiful rural mountains and was able to really see it for the first time. But I too was very interested in paleontology for a long time before realizing that that's not really a career path.

David Valerio: And not going to pay the bills. Yeah, so tell me about growing up in New Jersey and what your relationship looked like with nature. I've spent very little time in New Jersey. From the stereotypes that most Americans have about it, it's not exactly the most nature-filled place and you already alluded to that. But I'm curious, you know, how and when you did get out there and sort of what were some influential experiences in that regard.

Elias Ayrey: I mean, it's a perfectly pleasant place and there is plenty of nature preserves in New Jersey. And certainly my parents took me to those as much as possible. But, you know, at the end of the day, these are just kind of like aesthetic buffers that are left behind. Most of the nature preserves are just little squiggly lines between different housing developments. So as much as I enjoyed being in them, it wasn't quite the same as what I encountered later in life when I was able to interact with real, wild landscapes. But I think my Mom did a very good job of still keeping me interested in the nature that New Jersey had to offer.

David Valerio: Yeah, that makes sense. So tell me what it was like moving to Maine. You went to Maine for college and you mentioned that's where you got into nature more in depth. How did you end up going to the University of Maine? That seems like an interesting move from New Jersey.

Elias Ayrey: Well, I guess I went to SUNY Binghamton first as an undergrad, in upstate New York, which is also a very beautiful place. But then for my master’s and PhD, I went to Maine. Maine is really unique. It's still kind of my favorite place on Earth. We talk about moving back there all the time because the whole state feels like a small town and everyone knows each other. Wilderness is just a mile away. If you want to go out and just be completely by yourself around nature, all you have to do is kind of drive in a couple of miles in any direction and you'll get there. So it's a really beautiful place to be.

David Valerio: When going to SUNY, did you expect to be in forestry? Or you already said this. You didn't expect to be in forestry. You just happened to sort of get into it. And then you're in an area where, okay, let me continue to follow that path.

Elias Ayrey: I mean I was really interested in ecology. I got my undergrad degree in ecology at SUNY Binghamton. I wasn't really fixed on any particular type of ecology. Well, I really did enjoy paleobotany. And in fact, I still do enjoy paleobotany, which is basically the geological history of how plants evolved. It's a fascinating story filled with ups and downs that have a lot of drama to them. When I graduated, I realized I needed a career path that was more grounded. I realized it probably wasn't marine biology and it definitely wasn't paleontology. I looked at the University of Maine because I thought I could get a set of skills that I could actually make a career with, and get a job with. I certainly couldn't get a job when I first graduated undergrad with just an ecology degree.

David Valerio: Yeah. I guess when I think about ecology majors, I think of them maybe working for in environmental permitting for like engineering firms. But that's not exactly the most interesting line of work out there.

Elias Ayrey: Yeah, and there's not even that many jobs out there like that. And even those engineering firms want somebody with more experience than just like the theory.

David Valerio: They want in field work experience, like how do you actually know how to go out and core. All that kind of stuff.

Elias Ayrey: Yeah, it's a tough degree. Don't go into ecology kids, go into a related field.

David Valerio: I had a question about how you got into remote sensing in particular. You mentioned you were looking for a career path that you could make money in and also deals with nature. Forestry seems like an obvious answer to that. But how did you get into applying satellite imagery and remote sensing techniques to that particular subject?

Elias Ayrey: In addition to liking ecology, I've always been really passionate about technology. I've always kind of just played around with technology in my spare time. So even as an undergrad and as an ecology major, I certainly didn't need to learn how to code or anything like that but I did. I took a bunch of really like offbeat, kind of more engineeringy courses and really enjoyed them.

So I went to school for forest ecology at the University of Maine for my master's. When I got there I was kind of presented with two different options. One of them was a very boring forest ecology degree in which I was kind of shoehorned into one of my professor's projects. Even my professor didn't like that project. It was more or less just like studying cedar regeneration, which was very uninteresting. The whole thing is just driven by the fact that deer eat a lot of cedar in the wintertime. Or the university had purchased a very expensive LIDAR data set without having the slightest clue what they were going to do with it and without having anybody who could actually use it. I was the only person in the department who knew how to code at the time. So my master's advisor really pushed me toward remote sensing because I think he saw my enthusiasm for technology and my lack of enthusiasm for cedars.

David Valerio: Amazing. How did you find that transition? You mentioned already having an interest in technology and coding. How did your view of the world shift as you moved into remote sensing? I've done a little bit of GIS here and there, was never an expert or anything, but it makes me think about the world on different spatial scales in a more rigorous way than I might have without having any of that kind of background. So I'm curious what your experience was like getting deeper into that and examining the natural world through the lens of this technology.

Elias Ayrey: That's exactly right. It really kind of expands your spatial lens, and I spend a lot of time looking at maps, even in my spare time. A couple things came out of that program. First of all, during my master's, I got a pilot's license because a lot of the UMaine remote sensing group had pilot's licenses so that they could acquire aerial photography. Although I really used it very little during my graduate degree, it's kind of continued with me as a passion. I think that also kind of couples with what you said. Being a pilot really shrinks the size of the world. You can really visit a lot more places and see a lot more things, in a way that a lot of people can't. Even just like moving to a new area I'm able to get a sense of what's cool about that area very quickly relative to, I think, others.

I think another thing that shifted is, most foresters who you'll talk to will say kind of quasi-regretfully that they just can't see the forest the way that they used to anymore. And I think I definitely fall into that grouping in that no matter how hard I try, walking through the forest is still an analytical exercise even when I'm like trying to really disconnect. Because it's really just a matter of like asking myself, okay, what's the status of this forest and what could be done to improve it and where are the invasives and like what does this look like from a satellite image? That's a little unfortunate and I've talked to a lot of foresters who express that same kind of regretful feeling that there's kind of no going back.

David Valerio: Interesting. I had a similar thing studying geology in undergrad. It was like, I couldn't look at a mountain in the same way. I enjoyed it a lot, actually. Because it felt like when I would drive, like when I went to Zion National Park or something, I appreciated the beauty and just the stunning grandeur of this natural landscape. But having the geological lens and that timescale perspective made it feel even more crazy, if you know what I'm saying. Like, oh, wow. These rocks were deposited hundreds of millions of years ago and here I am in the 21st century viewing it.

Maybe that's just because geology is like, I think it's still one of the most poetical of the sciences. There's still a lot of qualitative thinking there. Obviously, quantitative reasoning, analytics, like geophysics, they've moving into the field. But relative to other areas of natural science, I feel like it hasn't been as… Like reductionism has not been as deeply integrated into it. Whereas from my understanding of forestry, like humans have been using forests as long as we've been around and it's been a commoditized industry for a long time. So there's like a huge incentive to really get the particulars right of—this forest holds this amount of wood and it can be harvested at this rate, such that when you bring on that scientific lens you really are analyzing it in a much deeper way, perhaps. I don't know if that's true or not.

Elias Ayrey: I agree. I think it's a double-edged sword. I don't think I ever looked at old growth forests in the same awe that I do now, before I got a forestry degree. But I do think a lot of forest history and a lot of our forests tell fairly sad tales about mismanagement in the past, or about where invasives and climate change are going to put them in the future. Maybe that's just my own persona.

David Valerio: No, I see that. I mean I had a similar thing. See I had no idea about forestry as an industry before starting to work in carbon markets. I started working at a new registry and was tasked with writing a forest carbon protocol, even though I was a freaking oceanographer for God's sake. But yeah, I learned a lot about for—I learned something about forestry pretty rapidly. My wife and I got married in that time. We went on honeymoon to the Pacific Northwest and I was noticing, I saw the clear-cuts. I saw like the way it was managed and I definitely felt a sense of... And I don't know if this is like the accurate view given that forest management is really complicated, but I felt sad because I was looking at these forests and walking in them and I was like, man. I was just thinking about the history of all these old growths that were completely devastated or something.

So, maybe part of it is like geology is such a historical science. I mean, we exploit geology all the time. Obviously, oil and gas is a thing. But it's not something that you really... Spatially, it's not something you... Well, that's not true. I was going to say like, you know, you go to the Appalachians and you look at like the destruction, like the old coal mines, right? Where they just tore off the top of mountains. But forestry, it's like very obvious that this has been managed for a long time and like somehow it feels more present than perhaps geology does. Because geology makes you think on these really long timescales, whereas forests are here now and we're going to think about how they're evolving going forward over time, perhaps in a more rigorous way.

Elias Ayrey: The timescale is an interesting point because I think geology is much longer timescales than forestry, but forestry is much longer timescales than most other biological sciences. We're generally talking timescales longer than a human lifespan, so I think that forests are often impacted by humanity's fairly short term thinking. I think that comes through when you kind of know what you're looking at.

David Valerio: Yeah, I mean I think about this too with relation to like agriculture. Like annual crop harvesting, it's pretty obvious that humans are really managing it. Those are mostly annual cycle processes, although obviously there are perennial agricultures and stuff, but most of like the dominant food crops that we use nowadays are annual. So it's like pretty clear, oh, this year the harvest was terrible. This year, the harvest was great. That is more aligned with human timescales of thinking about stuff.

Whereas, like you said, forests are more on like that decadal timescale, which is somehow still more graspable than like the geological millions-of-years timescale, but it still seems too far away for people to act on it. Similar problem as climate change, right? Obviously we're seeing effects right now, but like the baked-in effects are really, or the strongest effects are going to be felt in decades. So you can have companies making claims that they're going to do something about this, but they’re in 2050, not right now. So it's like this interesting mesoscale time period that seems like it's particularly hard to think about. It's interesting.

Elias Ayrey: Yeah, I agree. And I think that's also why some of the like statistics and tools in forestry are just so complicated because you need to be calculating things decades out from now if you're a forestry company.

David Valerio: Right. And whenever you get to those longer timescales, it's just like stuff gets crazy pretty quickly. Actually, I wanted to go back to something earlier in the conversation. You mentioned you're a big fan of paleobotany. What's your favorite era of geological history for paleobotany? What do you think is the craziest, most interesting part of Earth history when it comes to plants?

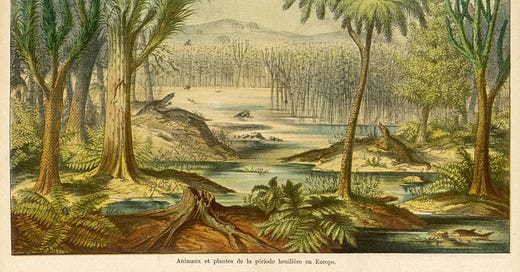

Elias Ayrey: I definitely think it's like the early days when forests were first evolving because there were just so many like weird evolutionary experiments. If you look back at like the Devonian or the Permian or the Carboniferous, you just see like enormous amounts of like wacky types of plants and trees that were popping up. And one good example is about 380 million years ago, there were mushrooms that were more than 30-feet tall. To this day, scientists don't really know why mushrooms were getting that big. There's a bunch of really cool hypotheses, like maybe they were gigantic solar cells for algae. Like they were in some sort of symbiotic relationship there with algae. Or maybe they were gigantic smokestacks to spread their spores across the world. Yeah, I mean there were many really wacky experiments back then that would make it really worth visiting if you had to go and visit a paleontological forest.

David Valerio: Amazing. I had never heard about that giant mushroom fact, but that's crazy. I mean the biggest thing I think about when I think about the Devonian and those other periods is just like coal, right? Like the fact there weren't fungi to eat all this aboveground biomass so it's just hanging out. But I hadn't really thought about the kinds of plants there. I know there's also like that big shift from... What is it, like conifers to angiosperms at some point? Which seems pretty interesting and remarkable.

Elias Ayrey: I want to say that was the Cretaceous that angiosperms first came about, but, um, could be the, uh…

David Valerio: No, you're right. It is the Cretaceous or something like that.

Elias Ayrey: I mean even the story that you brought up is a fascinating tale because I mean the first trees were not truly woody. Like, they didn't have wood as we would think of it. They were more like palm trees or tree ferns. They were kind of fibrous. And when wood evolved it immediately destroyed the climate. It immediately pulled all the carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere, piled up massive amounts of carbon dioxide into what are today coal beds. It caused a massive extinction of most of the life on Earth. So it was really this fascinating, like, boom and bust cycle of invention that is really, really cool to study.

David Valerio: Yeah, another example of that that I love is the Great Oxygenation Event. When we think about oxygen now, “Hey, oxygen is a good thing.” But for all the life that lived before that, it was literally poisonous gas, right? So you had all this history of life before, but then once oxygenic photosynthesis becomes dominant and it starts to change the balance of atmospheric chemistry, you're literally, like these other creatures are suffocating, right? It's amazing just how life manages to persist and change over time.

Another thing I love in geologic history is the Cambrian explosion. The thing I love the most about the Cambrian explosion is we still don't have an answer for why the heck it happened. You have like almost all the modern clades of fauna emerge within like tens of millions of years, maybe. Before, life wasn't really preserved. It didn't have hard fossils that you would see. And then after that something changes. That sort of contingency of Earth history… I don't know, I love the mystery of it as opposed to some other fields of science where you can like understand more and be like, “Well, I have a pretty good explanation for this.” Whereas studying Earth history or and Earth science in general, at some point you kind of just throw up your hands and be like, “Well, we don't know exactly what happened there.” You know?

Elias Ayrey: Yeah, exactly. It's kind of the only domain where you can discover your own species, and it's not that big a deal. Because there's lots of species that are not yet discovered in geologic history.

David Valerio: Amazing. Cool, well, next thing I wanted to get onto is like just how you got into carbon markets in general. Coming from this science background, getting into forestry, thinking that was going to get you a job. How did you end up in forest carbon in particular? What's the story there?

Elias Ayrey: Well, I guess when you graduate from a PhD you have a couple of options ahead of you. You can either go into academia, which may sound glorious, but is really just a matter of applying for grants endlessly. Most people kind of have a impression that academics and professors do a lot of really cool research, but this is really not the case. It's their grad students who do the research and they mostly just apply for grants and manage them. So that wasn't all that exciting to me. You can go into government and there are some really smart people that I was kind of working with at the time that went into government, like the U. S. Forest Service or the Bureau of Land Management and stuff. That's a nice stable career, but generally you're not going to have a huge impact. Like, the cool maps and science that you're doing will get lost to time.

I could have gone into the timber industry and I thought real hard about that. I did apply to a number of timber companies and came pretty close to accepting a job with one. I'm not philosophically averse to timber at all as long as it's done in a sustainable way. I think it's absolutely necessary and it's like our most sustainable material as a species. So it would have been interesting to go into the timber industry. But I thought that I could have the biggest impact if I went into carbon and especially if I went into carbon in like a tech startup type of scenario. So I ended up joining Pachama, which I guess was a tech startup at the time that was trying to like reinvent forest carbon. It was a very exciting time to join Pachama because I was employee number four, or basically about four or five. We kind of had a lot of funding and we had the whole world in front of us and I really thought at the time that we could really dramatically change the carbon markets if we incorporated some of the more advanced remote sensing techniques. I still think that to some extent. I just think that we didn't really end up doing that at Pachama.

David Valerio: Yeah, I had a similar story at my first job out of grad school. I guess originally when I got into grad school, I thought—I studied chemical oceanography was doing a PhD in chemical oceanography. You know, I honestly went to grad school not for the right reasons. I'm sure you're very familiar with people who are like, you're good at school, you're smart, and you don't really want to go shill for a company yet. So it's like, yeah, I'll go to grad school because that's what you do. Anyways, made that mistake. But I'd always had the idea of somehow turning my esoteric studies of isotopic tracers of oxygen and nitrogen in seawater into a company. First way I was thinking about it was like environmental impact assessments for deep seabed mining, which wasn't actively going on at the moment, but it's been a idea tossed around in the past since the seventies. And with the increasing numbers of electric cars people are going to use, people are now reexamining a lot more deeply. I'm pretty passionate about not destroying more ecosystems in the pursuit of addressing climate change. But that wasn't really a realistic one.

It was just by happenstance that a professor of mine at Rice was starting a new registry and I was brought on to work on it. I got really excited at first about carbon markets. I wasn't so motivated by climate per se, but I saw carbon and climate as a really awesome way to fund like broad-scale ecological regeneration. That's what I thought at first was going to happen. Then just sort of getting into it and seeing how the markets work changed that. Turns out actually that the company I got into was not doing what it said it was going to do and I got pretty cynical about it. I don't know. I just sort of rambled at you about, about my background coming into the market, but...

Elias Ayrey: Yeah, it's pretty similar to my own really.

David Valerio: Yeah, I guess, what was like the biggest takeaway you had from that experience in terms of what went wrong? You don't have to speak particularly about the company or anything, but just like the markets in general. Like, what was your key takeaway from that experience and how has it shaped what you've done since?

Elias Ayrey: Well, I guess I went into it thinking this was a technology problem because having just gotten a PhD in like all the cool forest remote sensing technologies and I saw around me that government and the timber companies were using technology that was far in advance of the carbon markets. And I went into the carbon markets thinking like, “Okay, the real solution here is to kind of introduce the markets to LIDAR and really automate the processes and get a lot more forests on board and make things a lot clearer.” What I discovered was that it's not a technology problem, it's a people problem. Because the carbon markets know that this technology is out there.

I think the big issues in the carbon markets are not so driven by technology, although it could help with scaling them. They're more driven by kind of conflicts of interest in the system and kind of willful refusal to change or adopt best practices. That's a much trickier problem than just saying like, “Oh, we've got a really cool new technology that's going to make things better.” I guess in my role at Pachama… I really don't want to bash on Pachama. They are a great company. They are a carbon broker, and they're trying to become a carbon project developer. They're one of the best places you can buy carbon credits, I think, right now. But they weren't really willing to push the bounds in terms of demanding that best practices be accepted. I was kind of dismayed to learn that the state of the market is where it is not because people don't know what to do, but because they haven't chosen to do the right thing—at least in my impression so far.

David Valerio: That's a really profound realization to have. Anytime you deal with humans stuff gets a lot more complicated and hard. What would you ascribe that unwillingness to sort of look the horse in the mouth? Is it purely self interest? Like, the way the markets work for most people in the market now, it's good for them economically. Is it just like a classic state of an established industry that doesn't want to change? To keep their own little rents or something? I don't know,what would you chalk that up to?

Elias Ayrey: I think that's a large part of it. I think that if we're realistic about the carbon markets, they are mostly dominated by like either a monopoly or a duopoly. Many carbon projects are only able to be created by a single registry. And I think that the markets were dominated by a set of very, um... Well, we know them today in the media as carbon cowboys, essentially. They were, and still mostly are, dominated by a group of financially motivated individuals who really want to squeeze as much money out of these projects as possible. And I think one of the dismaying things that I found when entering the carbon markets is that there are shockingly few carbon scientists, or climate scientists, in the carbon markets. The carbon markets are almost entirely dominated at high levels by I would say ex-finance people. Most of them are kind of in this for the right cause but they don't necessarily bring the kind of ethos of science to the work. They don't bring this kind of self critical nature that a lot of scientists are trying to have. They are really defensive in a way that I think a banker would be of his work,= rather than like a climate scientist.

David Valerio: I love that point and I think that it speak to so much about what's wrong, like, it's not just in carbon markets. It's in climate tech in general as well. The angle I particularly have seen the most of is sort of like the tech philosophy from San Francisco. Trying to apply a software mentality to solving climate change. When the Earth is a complex system that has moving parts that are atoms and are not bits. And sort of just that different paradigm for thinking about the world and how you shape it, I think is really dramatically affects what people do and how they do it.

So in the case that you just talked about, right? Coming from a finance mentality, you think of carbon as a commodity, and having carbon be a commodity implies certain things about how it should be done. Taking it as a commodity disconnects it from the fact this is actually an Earth system process. It's really complicated. And you need to apply really rigorous tools to actually try to quantify it well in order to even turn it potentially into a commodity. So, yeah, I don't know how much to like chalk it up to. I don't think it's ignorance at this point. It's, but it's like an unwillingness to accept that, you know... I get the critique of science in some ways, right? Like, we can be slow, but like the skepticism and that mentality which keeps you from doing stuff in a lot of ways is good, I think. It's a good mentality to bring to especially a complex Earth system like this one, where if you screw up, you're really going to screw up. But it's hard to think about that when you're trying to make money, I guess.

Elias Ayrey: Yeah, I mean, I think that it's a fascinating case study in how good intentions aren't quite enough. Because I do think most people in the industry have good intentions. Okay, so there are, without doubt, a number of high-level players who do not have good intentions. To some extent they've been purged from the industry over the last two years like the CEO of Verra has been fired and like so has their PR goon and stuff. But the vast majority of people in the carbon market have good intentions, but we still end up with this weird situation where... I think because they, sometimes people lack the bigger picture of what carbon credits are doing and trying to do, they will maybe sacrifice the integrity of the entire institution so that their little thing can work out.

One very common example, I think, is that project developers know full well that they're rigging the numbers, that they're getting too many credits. But they really, a lot of times, they really, really want their project to work. They know that this is the only way that this forest is going to be conserved, and that this is the only way that these indigenous people are going to get paid. So they're happy to rig these numbers because these are really esoteric numbers, and what do they really mean anyway, compared to protecting this one piece of forest that they're looking at. And as this happens more and more, a lot of really bad credits get put on the market, and the value of carbon credits goes down because it's kind of inflated with bad credits. That just causes people to need to rig the numbers more in order to make the finances of their project work. And good players then get driven out. Because if you're trying to go into this and get the correct number of credits and do everything right, how are you going to compete with another group that doesn't have those scruples, even if the other group is well intentioned?

There's a reason that the largest players in the carbon market are the worst. You know, if we look at the top carbon credit developers, I mean: South Pole, Wildlife Works, Anew. They do not receive very high scores in many of their projects on Renoster's platform. I think that that's because they're the ones who have lacked the scruples to really take a step back and say like, “Okay, this is too many credits.” I think it's just natural that in a system like this, in which you are able to kind of pick whatever numbers you want, the only people who are going to rise to the top are the ones that pick the highest numbers, right?

David Valerio: That makes sense. It's a race to the bottom, right? When the rules are so sloppy and ambiguous, the person who's least ethical is gonna dominate because they can just pump out a bunch of credits. Another thing I wanted to note is your point about good intentions. I agree as well and I've seen this in my career, where for people who really care about and love nature and want to protect it. This is kind of even the mentality I came into carbon markets with. Like the carbon was just a convenient vehicle for protecting and expanding ecosystems. But that chain of reasoning leads to a lot of sloppiness, as you mentioned. And the same thing applies to community co-benefits where you see the value that this project and these credits can bring to the people and to this forest. So you're like, “Ah, whatever the carbon numbers, they’re a little bit funky but it's okay. You know, don't worry about it.”

I think there is just like a fundamental ethical standard that people in the market either do or don't have where it's like, look these other aims of these projects are good. They're good for humans. The people that live there. They're good for the nature that is there. But if it doesn't accurately reflect the climate impact of what the project's doing, then I'm not gonna go for it because if we're selling something that's supposed to be about climate impact, it should actually mean climate impact. It's interesting just to think about who holds that. And I think this kind of relates back to the science versus business, maybe even non-profit view, where like for scientists, we care about truth. What is true? What is the most accurate statement we can make about this thing? Whereas in other fields or disciplines, maybe that's not as much of a priority when it comes to balancing truth against other priorities in what they do.

Elias Ayrey: Yeah, I agree. I think some of the biggest misbehaviors in this industry have been non-profits, who are otherwise great, or like people who are otherwise trying to do the right thing. I think one of the classic examples are non-profits enrolling land that they've already pledged, they've already conserved, right? So there should not be carbon credits issued to trees that are already preserved. But they feel passionately that they really need this money to like subsidize their program and to enroll more land. This is not what these credits are for at a pretty basic level. I mean to this day you can still get into pretty, I mean I can still get into pretty fierce arguments with these groups. These non profits who think that they should be getting carbon credits for trees that they protected decades ago. It even speaks to like a misunderstanding of what these credits are supposed to do that kind of permeates even the inner circles of this space.

David Valerio: I would love for you to expand on what your view is on what carbon credits are and what they're meant to do. What is their role in the world? What do you think they're supposed to do? Recognizing that a lot of people apparently disagree.

Elias Ayrey: People may disagree but I think at a fundamental level, as they're defined, they are intended to either remove or prevent carbon dioxide from going into the atmosphere during the duration of the project. And they can then be used to offset emissions put into the atmosphere by polluters. So I think that's a pretty simple explanation that does not cover things like conservation that was done decades ago, or trees that are planted for other reasons.

David Valerio: Yeah, you're right, it's a pretty simple definition. But I think that the history of this industry explains a lot of this confusion, right? Like, from what I gather…There should be a great history of carbon markets written at some point, maybe I'll have to do it.

Elias Ayrey: Oh, it would be a fascinating book. I've often been asked if I can write a book, and I'm like, “No, I don't know how to do that.” But it'd be great.

David Valerio: Well we should maybe collaborate on that at some point. Because as I mentioned, I'm a big history guy and I've thought a number of times that this industry needs a history. Because it's so complicated and like the background of it is remarkable. But like from what I gather, I think the conflation of climate impact, community impact, and like environmental impact has been baked in from the start. Let's just take the 1997 Kyoto Protocol as like starting carbon markets in some way. That's not strictly true. But from what I understand like that whole system was really meant as a way to funnel capital into the Global South in order to address climate impacts. I's supposed to not just do climate impact, but also address environmental and community co-benefits effects. So there is like this mixing of these three different domains that are very different, right? Like what is good for the climate is not necessarily good for nature.

You could imagine a world in which you go and like, I don't know, completely destroy some Amazonian rainforest, plant uber-super trees that are super-genetically modified to suck as much carbon out of the atmosphere as possible. Might be better for the climate, but obviously not good for nature. Or you think about like people. Like, okay, you can make the most effective carbon capture and sequestration machine possible, but it has terrible air pollution and it like kills the local communities around there. Good for the climate, not good for the people. But I think for carbon credits, it's been baked in from the start where this conflation has gone on. So the sloppiness is kind of just like fundamental to the way that it has evolved and it's hard to disambiguate and pull these things apart now since it was kind of baked in from the beginning. But again, this is why we need a history and maybe you and I will work on that at some point because I like to write and, uh… I don't know we'll figure it out.

Elias Ayrey: That would be fun. Yeah, I mean, there's so many adventurous stories in the carbon markets.

David Valerio: Yeah, it reminds me a lot of really excellent book I read, and I'm gonna blank on the name of it, it's a history of the oil and gas industry.1 Basically kicked off in the 1850s, and it's written by this guy named Daniel Yergin who is a really brilliant scholar. Amazing grand narrative history, one of my favorite ones. The carbon markets remind me a lot of oil and gas in that there's a race to the Global South to lock up land and, in this case, generate carbon credits. In the past, it was to exploit oil and gas resources. Concessions, literally, is how they were framed. Like 100-yearlong leases where the governments of these areas in the Global South, got paid rents, but they were not cut in at all on the revenues from oil and gas. It was purely in the hands of typically like Western—European, American—oil and gas companies who were reaping all the windfalls. However, in like the mid-1950s a lot of countries got smart and were like, “Well, hey, this is our land and we should be getting some of the revenues from this.” And so there is like a shift in power wherein they sort of clawed back on these concessions and started getting revenue-sharing agreements and then ultimately ended up nationalizing a lot of the oil and gas resources.

And right now in carbon markets, we are literally seeing a similar version of that, right? Where a lot of countries in the Global South are realizing, “Hey, there've been all these carbon cowboys (i.e. what in oil and gas are called wildcatters) taking money from us and let's go figure out how we can take it over.” That's emblematic of why I think history is so important in, I mean really everything, but especially even applied in industry. Because like you can see, or at least when I look at carbon markets right now, I'm like this is just a recapitulation of the oil and gas industry but in a different way. We're not emitting CO2 into the atmosphere, in this case. Hopefully. Maybe. Not all the time, as you know. But the fundamentals of how economics affect land use hasn't really changed.

Elias Ayrey: That's a very fascinating set of points. That is a very strong analogy, I think. Thank god there hasn't been… thank god South Pole hasn't created a coup in an African nation yet. Maybe it's only a matter of time.

David Valerio: Yeah, God forbid. I mean, who knows though. Zimbabwe, you're next. Relatedly, or I don't know if it's a related point, but related to some of what we're talking about. Where do you think your sense of justice comes from? I'll front this by saying I also have a strong sense of justice. Like seeing social depredation or the homeless—I've had compassion for people in all these capacities. And I ascribe it to my family being Christian when I was growing up and now I'm a Christian. So it's very clear where that comes from, that generally Christian attitude. Then I think in science, there's not like a sense of necessarily of justice in science, but truth is a thing. Like we got to get this right. And I know you have a very strong sense of social justice. Where do you think that comes from and how would you describe how that affects the work that you do?

Elias Ayrey: I mean, the glib response might be that I grew up with a little brother who probably got more of my parents attention than I did, and that certainly instills a sense of justice. I think it accumulated over time as I spent more time in the carbon markets. I think initially my goal was really justice around carbon. It was really around making sure that right was being done in order to combat climate change because that's obviously why I got into this field. And any carbon credit that's not having its own climate impact is actively harming the world's climate. But I think as I learned a lot more of what was going on in these projects, and I think at this point I've reviewed more than 200 of these carbon projects, it's hard not to feel a really personal sense of justice for what's taking place in these areas. I think we have to really remember that carbon credits aren't just this esoteric thing. They happen when a set of people on the ground decide not to harvest their timber. When they decide to give up a natural resource, or when they decide, for example, to no longer use their land for agriculture. That's a very real thing that people are giving up in exchange for these carbon credits, and oftentimes they're getting nothing in return inside these carbon projects. So I find that deeply infuriating, especially as a forest scientist, because I know how much these forests are worth to these people. And the idea that they are no longer able to harvest their trees as they typically would have and they've essentially been robbed of that right.

Obviously it hearkens back to colonialism, it hearkens back to blood diamonds, and, as you said, natural resource extraction from fossil fuels. So I think that my sense of social justice in this space creeped up on me as I read more and more of what was going on inside these projects. That's not to say all of them are bad. I think that's really one of the more interesting points about the carbon markets. I don't think there's any other field in the world in which there are such disparate outcomes. Because I think that there are carbon projects that are literally raising people out of poverty, giving them scholarships, sometimes literally putting food on their table. Then I think on the other hand of things, there are carbon projects that are clearly violating human rights. That's been demonstrated pretty clearly at this point. And that disparity in the carbon markets, without carbon purchasers even knowing that that disparity exists, really frustrates me. It really frustrates me to see, you know, the project that's raising people out of poverty selling for like maybe five dollars more than the project that is causing human rights violations. I don't know how anybody can't get upset by that.

David Valerio: That's a really interesting way to get into it. So it's really like practice and observation and being involved in the industry that motivated that sense of justice. Before starting at Renoster, I was mostly involved in carbon markets in the US and Canada, Mexico, some. But I was not exposed to the global carbon markets in the Global South. I had known that landowners in the US were getting screwed by carbon farming companies coming and signing them up for, “Hey, we'll pay you $10, $100 or $50 an acre or something (I'm making up the numbers) and we'll get your carbon rights for the next 10 years.” Not great, but it's not like these farmers are being killed, right? But then coming into this job and reviewing a lot of the reviews that you've done, I'm like, “Holy crap. This is a nightmare.”

And like you said, that disparity is the really remarkable thing. I think it's perhaps what makes carbon markets so controversial and sort of, like—I don't even know what kind of issue is like—it's one of these issues that like you either are uber against it or you're uber for it. You can look at the market and see completely different things depending on your perspective, right? So like if you're naturally more of a positive or optimistic outlook, you can see them and be like, “Well, look, but look at these beautiful carbon projects that are doing great things for the community and also having great climate impact. We got to figure out a way to make this work.” But then yeah if you have more of the pessimistic view, you see all the depredations and the human suffering and the lack of rigor around it. And you're just like, “This is terrible, burn it all to the ground.” I see how somebody could take either of those perspectives and it's just a hard issue to think about. Because I think carbon credits, they're just so abstract, right? Like you can't go touch, smell, feel it, hear it. In that way, it makes it much harder to like actually get to the heart of what's going on because you can't go touch it like a barrel of oil and be like, “Okay, well that's oil. Okay, that's timber.” Carbon credits? I don't know.

Elias Ayrey: I think it's fascinating how people in the industry are polarized on that exact same premise that you put out, which is that like people are either really, really for credits or really, really against them. I think I'm one of the few people in the industry who, walk a middle ground in that I try to acknowledge that many of them are good, but then most of them are bad. Everyone seems to have just picked a side and not allowed for any nuance.

David Valerio: Yeah. I don't know if this—it's probably just true throughout human history—but obviously we live in a particularly, or I don't know, maybe not obviously… Seems to us at least like we're in a particularly polarized time politically and on all other levels. I think your view is the pragmatic view. It's like, look, these can have positive impacts, but like anything else there are pluses and minuses. There are good ones and there are bad ones. And so to write off a whole category as either objectively great and amazing, and we gotta do whatever we can to make the carbon markets expand and grow while kind of turning a blind eye to the negative side versus screw this, this is terrible, let's just stop funneling any kind of money to any of these things. It's just the easy way to think about stuff. And I can sympathize with it.

It’s not to say like, “Oh, I'm holier than thou. I know what's going on.” It's just like again, maybe this comes back to the science. I'd be curious to see how that view is different based on whether you're like a scientist or if you're a policy or business person. Maybe, and maybe this is just like giving science too much credit, in being like, “Well, surely the scientists are the more rational people here,” but I'd be curious to learn about how that is segmented depending on where you are in the markets.

Elias Ayrey: Yeah. I mean, most scientists I've met are pretty pessimistic about carbon credits as they are today. Actually, as a student I was taught that most carbon credits were nonsense by my professors and I've come to learn that they're right. The reason that I stick with them and that I still want to see them work is not only because I have seen them work. Renoster, I think roughly speaking, we find that about 75 percent of the credits on the market aren't any good. But that still leaves like hundreds of millions of tonnes and dozens of projects that are really good. So I know that they can work.

But I think also I'm just deeply cynical of any solution other than carbon credits. I don't think human beings are going to think our way out of this. I don't think that companies are going to dramatically reduce their emissions or that people are going to make huge changes to their lifestyle. I do think that probably like there's maybe 10 to 20 percent of wiggle room that people are willing to make some cutbacks and stuff. But I'm not going to stop flying. I'm not going to stop taking vacations. And nobody else is, realistically speaking. So I really think that carbon credits are maybe the only way that are really viable to do something about climate change. Because I just don't see companies like dramatically shifting their supply chains or shifting their carbon emissions at all. It hasn't happened historically. Like we're not there, so..

David Valerio: I completely agree with you on the cynicism about people doing anything to actually, really reduce emissions. Like you said, there are some pragmatic ones where the economic tradeoff is not so crazy and, like, okay, we can reduce emissions marginally. But, and this is something I've noticed. This is just a general thing of climate and the climate industry in general, the amazing number of graphs that people will produce to somehow figure out how we hit net-zero by 2050 is remarkable to me. It's absolutely stunning that, “Great we've projected, or McKinsey has projected, that by 2050 we're going to hit net-zero,” and these things. It's like, where do we ever predict the future right? Literally! Like, come on.

There's so much magical thinking in the industry that I think is, it's actively harmful. A lot of people are really obsessed with figuring out how to do build out technologies to help companies reduce emissions and all that kind of stuff. But the economic incentives aren't there. The emissions keep going up. So if you took sort of a more realistic, in my view, approach, you're like, “Well, okay, so the emissions are going to keep going up.” What do we do then? If you take that as the standard approach, then you would come to something like your view, right? Which is more like, well, if humanity is going to keep growing economically. The Global South is going to keep using oil and gas because they should. They need the energy to provide for their people, right? I'm not going to stop flying. Like you said, I'm not going to stop driving. I like that stuff. If that's the case, then we should be doing more carbon sequestration, you know, carbon credits. Things to take it out of the atmosphere at scale.

Or focus more on something that I am personally very interested in now is like climate adaptation. Relative to mitigation and reduction, I hear like almost no talk about what are our actual plans for climate adaptation. Who's like proposing new ideas to solve the problem of a lot of the Indian subcontinent not really being a great place to live in 30 years? So I think a lot of this magical thinking is going to really bite people in the butt when we're like, wait, people are going to be dying. If these scenarios are going to go out in this way, we need to be figuring out and planning for how we move people from areas of the planet that are not going to be great places to live. I think that's an even bigger tragedy of this kind of unwillingness to look hard at the facts. It really affects what we do now and what we do now affects what's going to go on in the future. So yeah, I completely agree with you on that. You and I love to be the downers in the room. So, uh, I think that's a good thing.

Elias Ayrey: Yeah, I also think people often accuse carbon credits of like, they say that companies are not taking action because they're buying carbon credits and this is an excuse for them not to. I don't see that as being the case, but I also think that if carbon credits weren't so broken they would be selling for what they should be selling for, which is 30 bucks a ton and is like generally what it costs to do this kind of behavior. And at 30 bucks a ton, I mean, a lot of these companies would then consider taking more dramatic action instead of offsetting. So I think no matter what, you can stick with carbon credits and fix them and still end up with a better situation for everybody where there are fewer emissions.

David Valerio: I agree with that point. Another point that I think about a lot is like, they are not obliged to do any of this stuff, right? At all. Depends on the company, but for the vast majority of companies who are buying carbon credits it's purely voluntary. So if you think about it in terms of the view that this is literally philanthropy, that would change your approach to criticizing companies for doing it. And again, I'm not a shill for industries or anything. It's just like, look, they don't have to do anything. They are doing something by buying carbon credits. It may not be what you prefer that they do, but they're driven by economic incentives that you and I and everybody else on the planet are also driving them to do. It's a scapegoating that I don't think is very productive, and it imagines that corporations are moral machines which they simply are not. That's not what they're designed to do. And that's not what they're supposed to do, right? They're supposed to be making money. We're operating under a capitalist system where that's where the incentives are, so they're going to do it.

So if that's the case, we, people who care about this stuff, need to figure out how to guide those companies that are doing it. And that's really compliance and government regulations to set the rules for how corporates interact with climate. Climate is a negative externality, and it's a global commons problem, where it's not economically rational for any given operator to do something about it, right? Imagining that voluntary action is the thing that's going to do this... is kind of a red herring. I don't think people are doing it purposefully, but it just sort of it happens, and I don't think it's super useful.

Elias Ayrey: Yeah, I mean, I agree. Compliance markets have historically had a mixed reputation as well so I don't know. We just need better compliance markets, maybe.

David Valerio: Right, yeah. I think the answer is better compliance markets. The thing I was pointing to is just demand, right. Say what you will about compliance markets, obviously the protocols are not perfect and they suffer from similar flaws as voluntary markets. But the key thing about it is the companies have to buy stuff and they have to do something about their emissions, right? Because it's a compliance market. This is a view that I have increasingly come around, and I'm not a big government guy. Like I used to be like a philosophical anarchist. But if you want to do something about climate and if you want to fix carbon markets, they have got to be compliance markets. And they have got to be well-made compliance markets, as you noted existing protocols are not great. But otherwise there's not, there's just not going to be enough demand or incentive to do it.

Elias Ayrey: I don't know. I don't know if I'd go that far. We've interacted with a lot of companies that really want to get things right. You're talking from a very, Darwinian perspective, but I think a lot of companies are financially driven by consumer demand, especially on the left, to do something about their emissions. I think that to some extent, it's not necessarily the company's fault that they've been duped by these faulty carbon credits. They get all of the blame, but it's really like Verra and the project developers who have been creating these credits improperly. And I think to some extent we've seen a kind of resurgence and pushback against that. We're starting to see now coalitions, like the LEAF Coalition and the Symbiosis Coalition, of companies coming together and saying like, “Hey, you can't spoon feed us this crap anymore. We want real credits.” So I guess i'm a little bit more optimistic on on on that front.

David Valerio: Yeah, I can see that. It's interesting to bring up Darwinism because when I think about the natural world, I'm less of a strict Darwinian. I think that mutualism has a stronger, underrated play in terms of how humans and life evolves. I'm not a red and tooth and claw guy when it comes to the natural world. As I mentioned, I used to be a philosophical anarchist. So I like read some Peter Kropotkin who had a really interesting book about mutual aid and animal societies.2 I look at the eusocial animals, like the ants and termites. And humans, we're communal. I think that plays a much stronger role in evolution. But you're right that somehow when it comes to thinking about the human made economic institutions, I'm very cynical and I'm like these guys are just profit-maximizing machines. Perhaps if you're right, if consumers do radically change their choices, then that would change the incentives. But I just don't see like any leftists not driving their cars. Some people do and I admire them for it.

Elias Ayrey: Yeah, that's where my cynicism is too, but I buy offsets. I spend a lot of money on offsets and I know a lot of people who do. So people are willing to make some level of sacrifice. Maybe not everybody, but I don't know that we should rule it out as something that could have a dent on climate change at least, if not, you know, fix it.

David Valerio: Yeah, that's fair. That's fair. I had a question about what inspired you to start a YouTube channel. Because you've been very influential in the carbon industry through your YouTube channel. After that, what do you think has been the most interesting fruit of working on that media project?

Elias Ayrey: Well I push back that I've been influential. I've certainly been loud, but I'm not a mover or pusher in like the big, evil, dark, smoke-filled rooms in which things are decided. But I started my YouTube channel because I was just so fed up with people... I mean, it gets back to that disparity between outcomes and carbon crediting, right? The carbon credits that are selling for five dollars more than the carbon credits that are causing human rights violations. I really just wanted people to have the knowledge to be able to look at these projects and understand the differences between them. Maybe it's like overly optimistic, but I really did and still do believe that if people just kind of understand how these projects work then there can be a kind of consumer market pushback against all the fraud in the marketplace. They are incredibly complicated. I mean, as you know, they're made needlessly complicated by the carbon industry who really like to keep it that way. The more people know about how they work, the more they can navigate the market and select the good projects and and money can funnel in that direction. So I guess the most interesting thing to come out of it has just been like I'm surprised that anyone ever watches my videos. I am surprised that they tend to get like a couple hundred views.

David Valerio: It's funny, I've been on so many calls with you and you're always surprised when somebody's watched your videos and has been influenced by it. It's funny to me. But I get it. Like, I'm recording a podcast. Who's listening to my podcast? I've had people reach out to me saying they listen to my podcast. Like, oh, who's actually listening to this stuff? Who cares? So I get that. Personally, I can say that a big reason that I came to Renoster is because I was a big fan of your YouTube channel for a year before. And I was like, this is like one of the few guys actually saying real stuff in the carbon markets. I was really inspired by that. So I think your knowledge is power view, that's how I would view your motivation for starting the YouTube channel and also for doing Renoster. It definitely affects individual people and their thoughts. I've learned a ton from it, so it shapes how I view the market, and it shapes a lot of people that I know in the space about how they view the market. I guess the question is can enough people imbibe that kind of thinking and interiorize it, and then make that the demand lever that changes how things actually work? Is knowledge powerful enough to shift existing institutions and incentive structures that have been around for a while? I'd be curious to see if it works.

Elias Ayrey: Well, I don't think my Youtube channel has has done much of that, but I do think that at a larger level the market is trying to improve itself. And it is very slowly getting better. That is, I think, because the demand has increased for higher quality. I would put the credit of that mostly on these reporters who have been reporting on the market more than I'd put it on my YouTube channel. So I think it has had an impact. I don't know that it's had enough of an impact to really fix the problem, but certainly I think knowledge has driven a push for higher quality that we wouldn't have seen three years ago

David Valerio: That's a really well made point because the amount of power and impact that these various like bombshell news articles that come out about the carbon markets have is really remarkable. I think you would be a great one of those people, investigative journalists. This is kind of what you do already for with Renoster reviewing projects although we're getting paid for this, whatever. But like, there's a certain set of journalists and reporters, that you know far better than I do, who really do shift the way the markets work and the way that they do it. Maybe bringing your particular really rigorous scientific lens to that kind of work would be very valuable. What I'm saying is you should start a Substack. That's not what I'm really saying, but you could.

Elias Ayrey: Well, I mean I do. I mean I've helped most of them. I weighed in on the Guardian article before it came out. Myself and Renoster have provided assistance to reporters. This is something unique about our company is that we do share our data with reporters when they ask and that's because it's incredibly important that these reporters are able to do their job so that carbon credits can get better. The only way it's going to happen is if bad credits are called out and there's sufficient naming and shaming to make things better.

David Valerio: Amazing. So yeah, as we close, I just want to ask, going forward, what are the impacts you're trying to have in your career? And what do you think you'll do next? I mean, obviously we both work at Renoster. We're gonna do all we can to make it succeed, but everything fades. What do you think you would do next? Would you stay in carbon? Would you not? What are your thoughts there?

Elias Ayrey: Well, I guess what I'm striving to achieve is to fix the carbon markets. Obviously, I don't know that I'm going to achieve that. There's just so much inertia. The carbon markets have been extremely resistant to the obvious changes that need to take place. I often say that like Verra could fix its program with probably like six strokes of a pen. Rule number one is just like 50 percent of the revenues need to go to people on the ground. Rule number two is verifiers are assigned randomly. We can really easily fix Verra's program. It doesn't get fixed because of conflicts of interest in the industry. So that's what I'm trying to do. I'm trying to like create enough pressure that these conflicts are fixed and create carbon programs that are really doing what they say they're doing to really have an impact on climate change. You know, God forbid, if Renoster weren't to work out I don't know that I would stick in the carbon industry. Because I've been around it long enough to see the resistance to really obvious and necessary fixes. I don't want to spend my career in a corrupt industry fighting against the stream. So I might eventually like turn to one of those other professions that I had talked about such as like government or academia because at least there, while I wouldn't be having that much of an impact, at least there it would be kind of solid honest work. But who knows. Let's hope that Renoster works out and I can keep my job here and we can have a real impact on on the carbon market.

David Valerio: Amazing. Well, I think that's a great place to stop. Elias, thank you so much for coming on. I really enjoyed this conversation. It's always great to chat with you and just really appreciate you taking the time.

Elias Ayrey: Yeah, thanks so much for having me. I will really enjoy listening to this podcast in the future.

David Valerio: Awesome. See ya.

Share this post